The Parallel World of Sergey Kalmykov

Genius is the biological tragedy of an artist.

Sergey Kalmykov

Which one of the two parallel lines

that never cross and run away into eternity is

superior? Who is better, Repin

or Malevich? Or are both of them better?

Sergey Kalmykov existed in his

own special dimension, which was drastically different

from all the others. This was precisely

a case when the life of an artist interlaces with

his private life. Kalmykov had

the reputation of a village idiot, which saved him and

the freedom of his art from the

authorities and from imprisonment. What claims would

you lay on a village idiot? He

is harmless, quiet, walks along the streets wearing

motley, shabby dress and draws

and draws…In the Asian city of Alma-Ata where

the artist lived for over three

decades until his death in 1967, such people are

considered to be marked by the

hand of God, which required a sort of respect for

them. People got accustomed to

Kalmykov, to his self-sewn trousers with trouser legs

of different colors, to his scarlet

beret, to the empty rattling tins dangling from his fancy

jacket. With time he became a unique

part of the Alma-Ata city landscape, a kind of

a hummingbird in the Siberian taiga.

Whenever he could he would change

this decoration, although never abandoning the

overall decorative stylistics of

his dress. This is how he was portrayed by the late

Yuri Dombrovskii (in his novel

The College of Unnecessary Things): “The sun was

setting. The artist was in a hurry.

He was wearing a beret of burning colors, dark blue

trousers with stripes and a green

mantilla with bows. At his side hung a tambourine

embroidered in smoke and fire.

He didn’t dress this way for his own pleasure and

content, or for the people around

him, but for space, Mars, Mercury, for he was “the

first rate genius of the Earth

and of the Universe, decorator and performer at the Abay

Opera and Ballet Theatre, Sergey

Ivanovich Kalmykov”, as he used to call himself.

You would agree that such a figure

would not fit in with the stock image of the ordinary

Soviet worker, “a committed soldier

fighting for the victory of communism”. Had he

made for himself a capitalist type

checked jacket and cowboy boots with high heels,

he would probably have had to face

administrative measures, even to the point of

being taken into custody. But somehow

it never occurred to anyone to arrest a

“first-rate genius” of the streets

with his easel”.

“He would work day and night”, continues

Dombrovskii, “and not for his

contemporaries, but for future

generations. He didn’t care about the 21st century, he

would work for the 22nd century.

He would produce his grandiose cycles, hundreds

of canvases and sketches in each,

for those remote descendants… He did not show

anything to anyone, perhaps he

just did not have time”.

Neither did he sell his works to

anyone; sometimes he would give them as presents to

people he thought pleasant, but

never sold them. Poverty in his everyday life followed

him closely; he knew undernourishment

and starvation. Every year milk and bread

were his main food. The furniture

in his hovel was made up of packs of old

newspapers tied up with string.

Sure of his destiny, Kalmykov wrote not without

irony:

“One should not be afraid of geniuses.

They are nice people. I can judge by myself.

I am a genius myself. I have no

superiority complex. I am very modest and poor.

Ordinary people in all probability

imagine a genius in the following way: High salaries.

Popularity. Growing fame. All having

manuscripts, money. Each nursing his wealth.

But we modest professional geniuses

know: A genius means torn trousers. It means

socks with holes. It means a worn

out coat…”

Before his death in a hospital ward

he would marvel at the taste of hot food.

Sergey Kalmykov belonged to the

masters of the Silver Age of Russian Culture and

was probably the only one of them

who survived till the late 70s, nearly till our own

time. He was a contemporary of

Malevich and Kandinsky, Shagal and Filonov.

In 1910 he entered Zvantseva’s

school in Petersburg where he attended classes

conducted by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky

and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. After a year of

study Kalmykov produced the picture

Red Horses Bathing. Petrov-Vodkin highly

praised this work of his disciple:

“Kalmykov was like a young Japanese who had just

learned to draw”. Well, and the

“young Japanese” held his “Red horses” in high

esteem… About a year later Kuzma

Petrov-Vodkin showed his famous work The

Bathing of the Red Horse, that

in a certain sense became a symbol of the Russian

avant-garde along with the Black

Square by Malevich.

Kalmykov used to chafe: “For the

information of the future compilers of my

monograph, it was me whom our dearest

Kuzma Sergeevich depicted riding this red

horse! Yes, yes! The soulful boy

depicted on this banner represents no less a person

than me”.

In 1918 he left Petrograd and moved

to Orenburg where he had spent his childhood.

Kalmykov was convinced that the

roots of world art go back not to Paris but to

Babylon and therefore his place

of permanent residence seemed to him to be of no

particular significance. The scurry

and scramble of life in the capitals would irritate

rather than attract him. Besides,

it was a tumultuous time… Kalmykov was right: had

he stayed in Petersburg or in Moscow

he would hardly have been able to live till old

age, outliving his famous contemporaries

by a full quarter of a century.

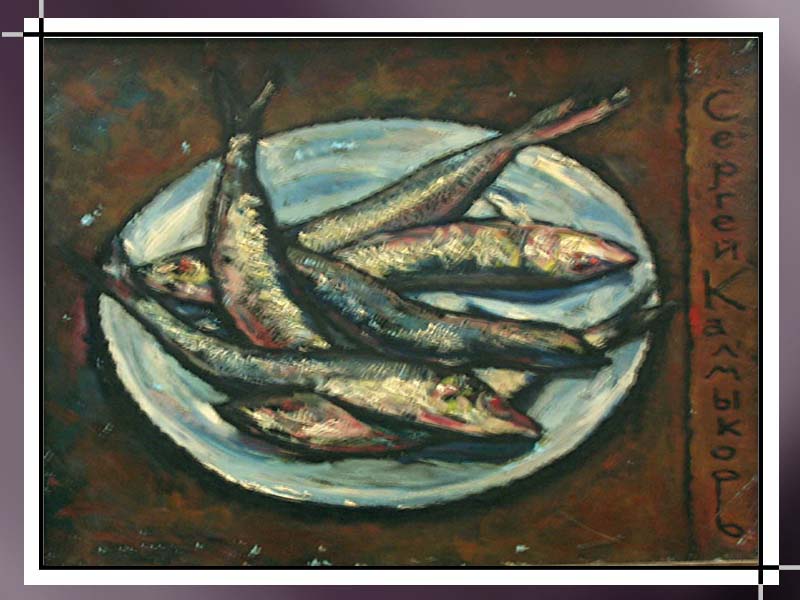

According to very rough estimates,

Kalmykov left a legacy of over one thousand five

hundred works—drawings, prints,

paintings—and nearly ten thousand pages of

manuscripts, that look like a kind

of self-publication: sewn, collated and bound books

that were lavishly illustrated.

All of these texts without exception were made by hand;

every letter a drawing, every page

presents a complete composition. It included

essays, art critical works, philosophical

speculations and novels. The Pigeon Book,

The Green Book, The Factory of

Booms, The Moon Jazz, A Thousand Compositions

with Atomic Reflectors. He was

concerned about the future and the past, about

Space and the Atom, about Peace

and War. He wrote: “The war with the Japanese

and afterwards admiration of Japan.

Admiration for the Germans and afterwards war

with Germany. Fluctuations are

going on not only in me. And now, too. Russia is

between the East and the West,

between Europe and Asia, between the past and the

future”.

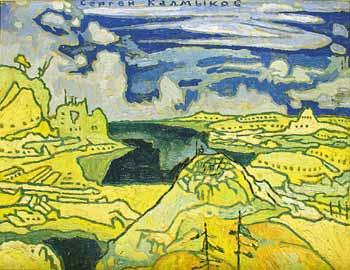

And yet, Kalmykov was closer to

the future than to the past with its Babylonian

cultural roots. Working in different

genres of Fine Art he still preferred expressive

graphical compositions and monofigure

painting to the descriptive city landscape.

Under the famous “mosaic sky” realistic

details were presented against a fanciful,

unreal background. He did not ignore

abstract compositions: for a long time his

famous Suprematist composition

was ascribed to Malevich, and later on to

Chashechnik; only recently the

efforts of dedicated researchers have yielded

documents proving Kalmykov's authorship.

In his famous abstract triangular

paintings Sergey Kalmykov is in a state of a dialogue

not with Kazimir Malevich but with

Vasily Kandinsky. Kalmykov opposed The Theory

of a Square to The Theory of a

Point, which in his opinion was the basic dominant

element of Fine Art. Kandinsky

is close to him not only in his painting but also in his

consideration of the importance

of the musical pause, which is the equivalent of a point

in a musical work.

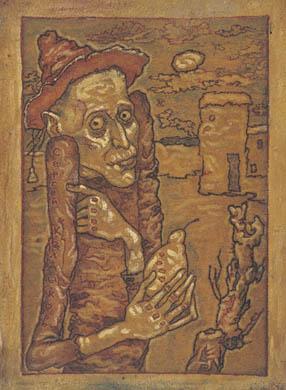

Kalmykov drew brilliantly and produced

about thirty self-portraits during his lifetime.

The last, made two months before

his death, was completed in the “Monster style”

he invented. The gallery of self-portraits

up until outlines the whole life of the master,

and by its level and emotionality,

is probably comparable with the artistic achievement

of aVan Gogh.

Sergey Kalmykov lived in a terrible,

surrealistic epoch, when people believed that

black was white, that Dzhugashvili

(Stalin) was the best friend of children and an

authority in all sciences, that

communism would be established by the 80s of the last

century and all citizens would

be absolutely happy and content. Kalmykov perceived

life as it really was: impenetrably

grey with stains of blood. Thus he wrote: “Just imagine

that millions of eyes are watching

you from the depths of the Universe: what would they

see? A colorless dull and gray

mass creeping on the ground and suddenly, with the

effect of a sudden shot a bright-colored

spot. That is me stepping out into the street”.

Sergey Ivanovich Kalmykov thought

he would live at least a hundred years. He died

at 76 years of age. Nobody knows

where his final resting place is.

|

![]() © 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.

© 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.