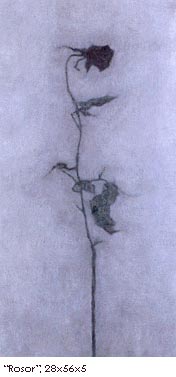

... bodes the death of the rose

The so-called Nerdrum School, the Norwegian new-traditional school of

painting, includes a stylistic feature that has always seemed foreign to

me, namely a striving for exactness. When painting a hand, how interesting

is it to achieve anatomical correctness as long as the image is not imbued

with life? I think this observation can be generalized, and it has forced

the more independent talents among young figurative painters to move beyond

academicism and toward expression and stylization. Both Baroque-influenced

Thomas Knarvik and the increasingly minimalistic Sverre Koren Bjertnæs

have moved in this direction, and - although steering a middle course

- the Swedish artist Christopher Rådlund has as well. Of course there

are motifs and motifs. "Paint me a rooster", the Chinese emperor commanded

his eighty-year-old rooster painter while the palace guard pushed the artist

to the floor beneath a raised sword. Legend has it the result was dazzling,

but one cannot capture all motifs in a few lines like one can a rooster,

(a wind-torn pine, a mountain). Not the motif of the human figure. Our

signs can carry everything except ourselves. In my opinion, it is precisely

in his paintings of infants that Odd Nerdrum, in his slightly finical manner,

comes closest to a timeless mastery. These paintings are form and light,

but also entirely their motif's content.

The human figure is currently absent in the motif world of Christopher

Rådlund, and I believe this is related to the problems raised above.

Many years ago, I saw huge charcoal drawings by C.R. at the Södertälje

Konsthall. On them, human bodies come to life and open up. They are kindred

to Käte Kollwitz's pictures, but in contrast to hers, movement is

directed outward, not inward, not toward the body. Like a sailing ship

with rigged sails, the figures in these pictures glided ever further away

from the artist, and he has since then moved on to picture solutions which

exclude the human figure entirely. Now whatever he wishes to express about

us and our situation must be said with the help of external objects in

traditional genres, the landscape and the still life. But can one call

his skull motif, the cranium, an external object? Like a tankard or a bone-white

cup it rests there, inside our identity's cheeks and eyes. Anonymous down

to its hard core, but personally carried out. Just as one can see in the

old masters (Titian, Velazques, Goya...), the skull on the canvass becomes

more than a skull. It has a surplus, like a lamp. The mystery in the picture's

skull is how these wide, organic, almost plantlike lines are able to create

a crystalline brittleness. It belongs at the same time to the human sphere

as it does to the sphere of nature. Is this then the final word about man,

that he is in fact nature? All the same it is difficult to discover any

classical, nature-tuned harmony in the aggressive jaw that sinks its remaining

teeth into the green dark of evening, before the night's shower of ashes.

Irrespective of the picture's "natural" motif, we are reminded that painting

is always culture and culture is always decadent. Yet another transformation;

the nature painter reveals himself as a commentator on the contemporary.

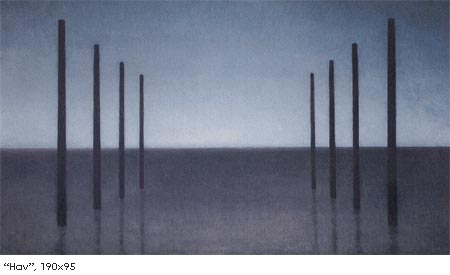

In the armour-bright "Hav" ("Ocean"), the perspective of infinity becomes

intimate and nauseating. Twilight and daybreak lie in wait for each other

- the snake that is about to bite its own tail. The observer feels both

hope and imminent catastrophe. This is truly a painting for the turn of

the millennium.

Like the romantic churchyard painters of bygone centuries, C.R. is

above all an elegist. Despite their lyrical qualities, his many cloud pictures

are executed with monotonous gloom. His roses are relics of roses, his

landscapes songs of mourning for lost landscapes. In her book Soleil

Noir - Dépression et Mélancholie, Julia Kristeva asks

whether disillusion can be beautiful. In her answer, Kristeva points to

a historical example, the Lutheran uprising, and how artists like Hans

Holbein did not want his drawings to glorify the gold and finery of the

rich. She writes: "A new idea was born in Europe ... the idea that the

truth is austere". This observation led Kristeva to consider the social

protest that sorrow can contain. C.R. wrote to me while traveling on a

grant to Scotland, Wales and Ireland. I saved a letter of his from Ireland.

He is full of sarcasm: "Celtic mood, Celtic spirit, Celtic life and so

forth. Mildly put a bit exhausting for a pilgrim. I hadn't realized I was

going to visit Holy Lands, not this cheap and easy sleight of hand with

myths and heritage. The future? Dublin will change its name to Bodhran

(the hand-drum in traditional Irish music) and hamburgers will be sold

under the name McCeltic". It wouldn't be difficult to translate his critique

to Scandinavian conditions. How everything down to the most genuine (be

it the Hardanger, fjeld-rapids or Odd Nerdrum paintings) is transformed

into the shabbiest form of commerce.

For C.R.'s most recent exhibition in Oslo, the artist requested a calligrapher

to decorate the posters announcing it with classicizing calligraphy, using

these lines by the Swedish poet Pär Lagerkvist: "Let my shadow disappear

in yours / Let me lose myself / Beneath those great trees / They who entrust

themselves / To the heavens and to night." This is reminiscent of the two-way

movement in any artist's protest. On the one hand there is a lingering

in the sorrow of the self and a negation of the world (as it appears),

and on the other hand an unconditional capitulation before nature or the

powers of nature. To my mind, this intrinsic inner conflict is most clearly

addressed in the paintings of rose stems. Their dried-up brittleness makes

me think of Giacometti, who would study dust formations in his atelier.

In his article "L'atelier d'Alberto Giacometti", Jean Genet writes of an

art that must move through the porous walls of the shadow realm. Genet,

who did not love roses, but did love the word "rose", has all the same

seen their pale light. I see it. It is like the backlit chinks around a

heavy door. Like Juliet's young lips when she awakens in the Capulet's

family grave. Coke cans are red, but lips are grey. "Her weeping was the

weeping of roses. I saw it." (Sigbjørn Obstfelder).

|

![]() © 2003-2005 Ars Interpres Publications.

© 2003-2005 Ars Interpres Publications.