Joseph Brodsky’s Rooms

Almost every summer from 1988 to 1994 Joseph Brodsky

spent a few

weeks in Sweden, and many of his works – poetry,

prose, plays –

were written or finished here. The book about

Venice, for instance

(Watermark), he worked on in a corner

room of the Hotel Reisen,

with the Baltic sea and the sailing ship af Chapman

before his eyes:

hence the salmon that “leap out of the water

to greet you”.

The room at the Reisen was an ordinary hotel

room, but rather big.

Not too big, but on the borderline of what Brodsky

would accept. Yet

he could work here; perhaps the suffocating

abundance of space was

compensated for by the view of the element he

loved the most: water,

this form of condensed time.

Rooms, the size and shape of rooms, were

constantly on Brodsky’s

mind – since he was constantly in need of provisional

spaces to be able

to work. He spent the summer in Europe, escaping

the humid heat of

New York, so perilous for somebody with a heart

condition. Those of

his friends who, year after year, did their best

to try to satisfy the poet’s

need to work in peace – in London, Paris, Rome,

or Stockholm –

know how difficult it was. Even for someone who

thought he knew

something about Brodsky’s preferences it was

impossible to foresee

how he would react to the proposed square meters.

Water, one would

think, a smashing view, zinc-grey waves – in

theory everything squared;

yet he would say no or could not make up his

mind, and the project

petered out in the sand.

A couple of summers he stayed as long as

he could, i.e., as long as he

could afford – usually a few weeks – at the

Mälardrottningen,

a hotel

boat anchored in the Old Town. The cabin was

small, maybe a bit too

small, but in this case the clucking proximity

to water more than

compensated for the obvious lack of space.

Two summers in a row he stayed in different

apartments around

Karlaplan, a residential area in the centre of

Stockholm. In one of

them, he retired to the maid’s room, although

the vacationing owners

had put the whole apartment at his disposal.

It felt better that way, and

in addition the World Championship in football

was in full swing and

the TV set stood in that part of the flat. The

other was a one-room

apartment, and it nearly ended in disaster right

at the threshold: the

walls were painted an ascetic white and decorated

with the sort of

“modern” art that Brodsky despised: “This century’s

stuff”, which has

only one function, “to show what a cheap, self-assertive,

ungenerous,

one-dimensional lot we have become”. In spite

of this, he stayed for

over a month and wrote, among other things, the

play “Democracy!”

That he stayed so long was partly due to

the fact that, with time, the

interior began to fascinate him: in this cross

between a mental institution

and a museum of modern art he found an explanation

of the quiet

Nordic lunacy he saw manifested in the films

of Ingmar Bergman. But it

was also an expression of an important trait

in Brodsky’s psyche: after

some time, he domesticated all spaces where he

lived, and moving out

was always a painful process for him, especially

if the work went well.

In any case, it was not because of a lack of

alternatives – after all, there

were always hotel rooms – or of delicacy: a person

who has fled the

palace of Fiat boss Agnelli has no problem abandoning

a one-room

apartment in Stockholm.

One year there was a summerhouse at lake

Vättern; but most of all he

preferred Stockholm and its archipelago: the

same waves and the same

clouds that had earlier visited his home realm,

or vice versa; the same

herring – if only sweeter – and the same vessel-widening

– if only

bitterer – vodka.* In a house on the island

Torö, with a mind-boggling

view of the razor-blade-sharp horizon, the poem

“Lecture for a

Symposium” with its aesthetic-geographic credo

was written in 1989:

But having loosened itself from the body,

the eye prefers to settle somewhere

in Italy, Holland, or Sweden.

But, as said, it mustn’t be too big, the

space where he was to live and

work. If there was a smaller house on the property,

he chose that. And in our flat Brodsky immediately pointed out his favourite

space: a dark

balcony facing the courtyard, about the size

of the cabin at the

Mälardrottningen, perhaps a bit smaller.

In any case, smaller than ten square meters,

the size of the space that

had for all future defined Brodsky’s view of

the ideal room. These ten

square meters were his part of the “room and

a half” which he had

shared with his parents in a communal flat in

central Leningrad and that

he has described in an essay – one of the best

childhood accounts ever

in English or in Russian literature. Here he

lived until he was exiled in

1972, and here his parents died, in the absence

of their son, some ten

years later: Liteiny pospect 24, flat 28.

“My half”, he wrote, “was connected to their

room by two large,

nearly-ceiling-high arches which I constantly

tried to fill with various

combinations of bookshelves and suitcases, in

order to separate myself

from my parents, in order to obtain a degree

of privacy. One can

speak only about degrees, because the height

and the width of those

two arches, plus the Moorish configuration of

their upper edge, ruled

out any notion of complete success.”

The construction of barricades, initiated at the

age of fifteen, intensified

as the books and the hormones made their demands.

By reshaping a

bookshelf – he removed the back but kept the

doors – Brodsky

created another entrance to his half: a visitor

had to make his way

through two doors and a curtain. And to conceal

the nature of what

was going on behind the barricade he used to

play classical music on

his record player. His parents learned to hate

Bach, but the musical

curtain fulfilled its mission and “a Marianne

could bare more than just

her breast”. When, with the time, the music was

supplemented by the

rattling sound of an “Underwood”, his parents’

attitude became more

condescending.

“That was,” writes Brodsky. “my Lebensraum.”

His mother cleaned

it, his father passed through it on his way in

and out of his darkroom,

and sometimes one of his parents would seek refuge

in his ragged

armchair after some verbal battle. “Other than

that, these ten square

meters were mine, and they were the best ten

square meters I’ve ever

known.”

Brodsky never again saw either his parents

or this Lebensraum, which

he almost maniacally tried to re-create in other

places throughout the

rest of his life. He never again saw the room

because he never returned

to his hometown; and he never returned to his

hometown because his

thinking – and acting – was linear. “A person

moves only in one

direction. And only from. From a place,

from the thought that entered

his head, from himself.” In short, because from

the age of thirty-two he

was a nomad – a Vergilian hero, doomed never

to return home.

Yet he was on his way many times, at least

in his thoughts. When, after

the Nobel Prize and, especially, after the fall

of the Tyranny, it became

possible to return, he was often asked why he

didn’t. His arguments

were manifold: he didn’t want to come back to

his home country as a

tourist. Or: he didn’t want to go on an invitation

from official

institutions. The last argument was: “The best

part of me is already

there: my poetry.”

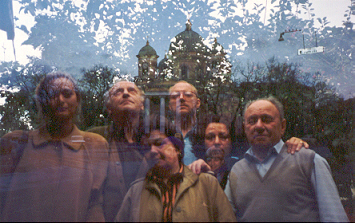

Photo: © Bengt Jangfeldt

Nevertheless, he came back. In January,

1991, a symposium about

Brodsky was arranged in Leningrad. One afternoon

we made an

excursion to the house with the room and a half,

and I took pictures

that I planned to send him to New York. This

will make him happy, I

thought: pictures of his old friends before his

Lebensraum. For almost

as strong as the poet’s nomad instinct was its

opposite: nostalgia.

Half of the roll had been shot in Stockholm,

and I finished it in

Leningrad. When it was developed, the pictures

turned out to be

double-exposed. And not one or two, as might

easily have happened,

but all of them.

The photos taken in Stockholm show Joseph

and his wife with my

family, and these had been projected on the pictures

from Leningrad.

On one picture he stands before flat 28, on another

he looks at the

balcony of the room and a half, with the Cathedral

of the Saviour in the

background. In this way, Brodsky returned to

his ideal space; if it

happened by means of a technical mishap, it was

perhaps because he

was the son of a photographer.

After spending some time trying to understand

what had happened, I

drew the only reasonable conclusion, i.e., that

somewhere in the middle

the film had changed direction and returned,

frame by frame, to the first

exposure – to the room and a half. In other words,

the film had made

the movement that Brodsky himself was incapable

of: back.

* Broskys’ favourite Swedish vodka

was Bäska droppar (”Bitter drops”), made on wormwood.

|

![]() © 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.

© 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.