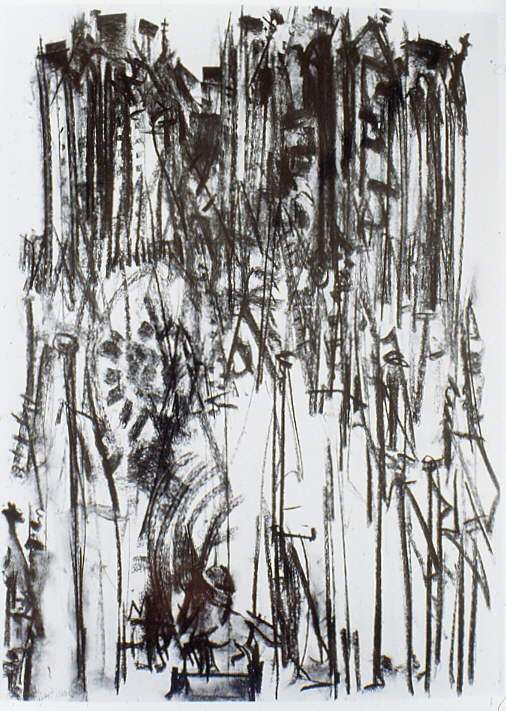

The English artist Dennis Creffield (b 1931) is probably

best known for his

drawings and paintings of buildings and cities. He

has at various times

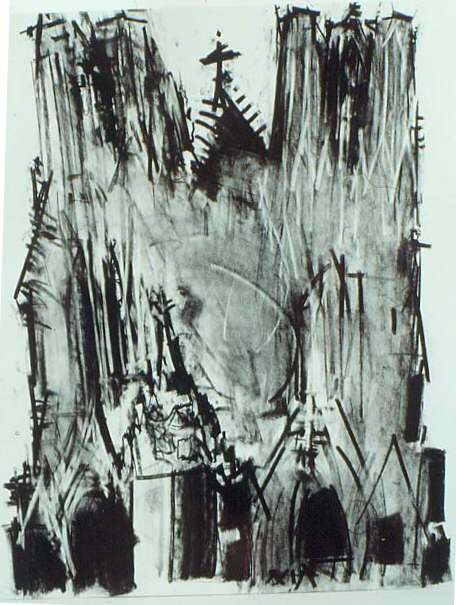

been commissioned to draw all the Medieval Cathedrals

of England (26) –

the major Cathedrals of Northern France – the Castles

of Wales – The Palace

of Westminster in London – the great English Country

Houses of Ickworth

and Petworth – the Desolation of Orford Ness and the

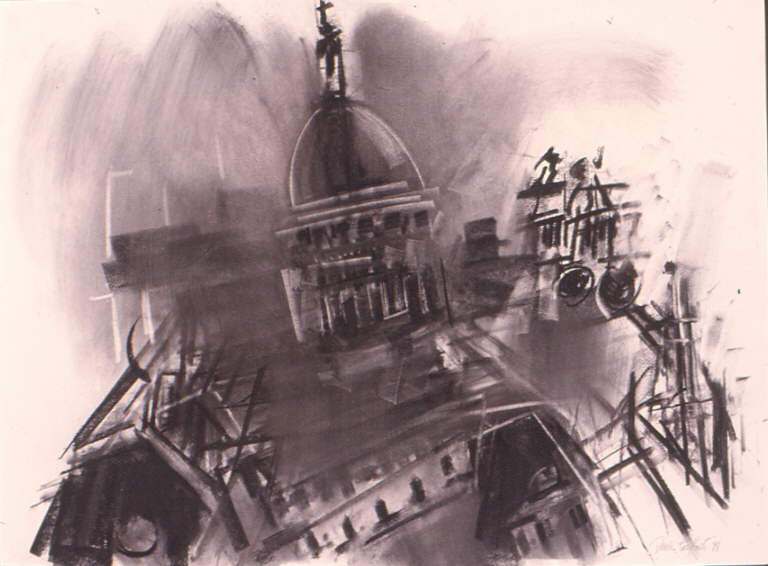

Cityscapes of London,

Manhattan, Hong Kong and Jerusalem.

The following are selections from his reflections

on the various problems

of drawing at some of these places.

“The Friend of Cathedrals and of Castles…”

It is not possible to get the complete expression...

of the apse of

a Gothic cathedral, into a picture, as the elevation

cannot

be drawn as a vertical plane in front of the eye, the

head

needing to be thrown back, in order to measure their

height, or stooped, to penetrate their depth.

Ruskin "Modern Painters IV"

This is a clear description of the inability of the academic

approach

to cope with the complexity of human perception. (The late –

Renaissance academy had – for the purpose of drawing and

painting – reduced visual perception to a static-one-eyed viewpoint:

geometric perspective.)

The medieval artist’s idea of the perceptual was as of a faculty of

imagina¬tive understanding. And so in his art space, time and

distance are not governed by measurement but by the relative

significance of the constituent parts.

I belong to the progeny of Cezanne – that self-described – “primitive

of a new art”. He inaugurated an era in which the very complexity

and uniqueness of perception is itself the subject of the painting.

I am not interested in creating an illusion of reality – nor in making

a

symbol of it. But in trying to find a substantial form for its substantiality

– an image of actual experience – the wound unbound.

____ ____

Yes, Ruskin — it is possible. To look up and to look down – and to

unite these separate moments of time and physical movement – by

means of the continuous imagination of memory.

I do not look at the cathedral as if through a letterbox – neither do

I

draw it so.

*

To describe my work I would like to reclaim the word

“impressionist”. It’s a waste that it should only be used to describe

the work of certain 19th century painters – who didn’t choose it

themselves anyway.

I use it in the way we do when we say – “that is impressive” or

“I am impressed”.

Here an “impression” is not a fleeting optical moment but a total

response. A perception in which eye, mind, body and imagination

are all one at the same time together.

Understood in this way I am an “impressionist”.

*

“Remember the impression one gets from good architecture, that it

expresses a thought. It makes one want to respond with a gesture.”

“Architecture is a gesture.”

These two thoughts of Wittgenstein’s state with clarity and

distinction my approach to drawing the cathedrals.

By gesture (I mean) the significant stance that characterizes and

identifies people and things. Van Gogh remarks that we can identity

an acquaintance from a great distance because we recognize their

stance. We recognize familiar trees and animals in the same way.

(This is not simply shape – the gesture is an animate principle.)

Each cathedral is a gesture – I respond with my gesture and the

drawing is a mutual embrace. (And the marriage of two minds.)

*

I find drawing extremely difficult. I don’t do it because I enjoy it.

But because it's the only way that I can understand things.

This writing has been an agony – words slide about and don’t have

any density – no reality in themselves – only in what they mean.

Only drawing is real - and I only feel real when I draw.

*

“Architecture immortalizes and glorifies something. Hence there can

be no architecture where there is nothing to glorify.”

These drawings are my glory to their glory, which came from the

glory of God.

London, 1987

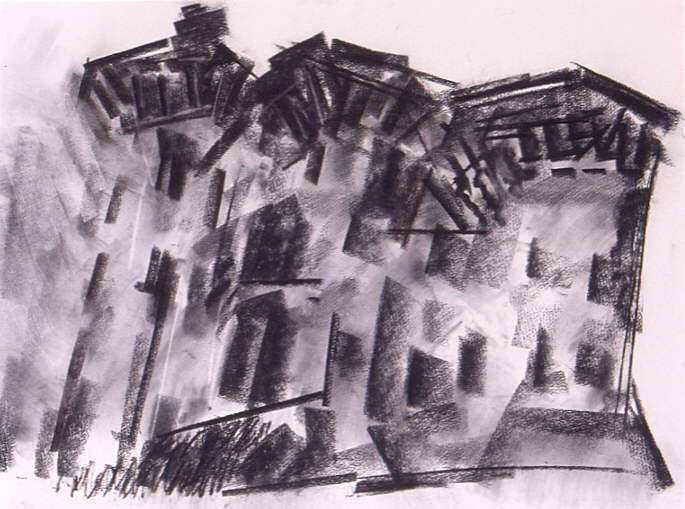

Having drawn all the English Medieval Cathedrals for the South

Bank Board 1987-88 and most of the major Northern French

Cathedrals, thanks to David Astor in 1990, I thought I was finished

with medieval architecture as a direct inspiration and subject for

work. However, the invitation by the Globe Gallery in Hay-on-Wye

to draw the Welsh and English Marcher Castles re-aroused my

interest, because most of them were probably built by the same

workers and masons that constructed the cathedrals.

What has been called the second Stone Age was begun by the

Normans. (According to Jean Gimpel from the eleventh to the

thirteenth centuries more building stone was quarried in France than

had been mined throughout the whole history of Ancient Egypt!).

Castles must be built quickly, strongly and soundly; this accelerated

the technological knowledge that extended from quarrying,

recognition of good quality stone, transport and the swift and

masterly working of the material. So, ironically, the expertise

needed to build the cathedrals was what we would now call a

‘spin-off’ from Warfare.

I had great difficulty in drawing the castles. I prefer to draw

functional buildings and whereas the cathedrals are still used for

their original use and are generally complete structurally, the castles

(except where they have been converted to domestic use), are

redundant in function and ruinous as structures We don’t even know

very much of the detail of how they were used, except that they

were centers of power and commanding physical presences in a

then lightly populated countryside. They are almost as mysterious

to us as Ozymandias’s “...vast and trunkless legs...”. In consequence

they have become places of our imagination – an imagination –

largely dominated by a nineteenth century vision of – Fantasy,

Romance, Symbolism and the Picturesque.

I have followed this fantastical line but been not only inspired by

Tennyson and Turner and Maeterlinck but also medieval paintings,

my own remembered toy castles and also those innumerable

sand-built-bucketed structures, which took half a day to build – and

if you were lucky, slowly eroded (the moat filling up) by the

incoming tide – if you didn’t have to go home before! But more often

by horrible boys who leapt over them and kicked them down.

A small sad echo of what did eventually happen to these great

buildings.

Hay-on-Wye, May 2002

Painting from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

and “Mozart” series by Dennis Creffield

|

![]() © 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.

© 2003-2011 Ars Interpres Publications.